- Whereas in other areas at this time growth was brought about by migrants from Nottingham, driven out by conditions and prices in the town, the growth of New Sneinton was one and the same with the growth of the town. Houses built some distance away on John Musters' land at this time were of a better quality than those on Lord Newark (aka Lord Manvers)'s land which shared the poor quality of adjacent houses in the town.

|

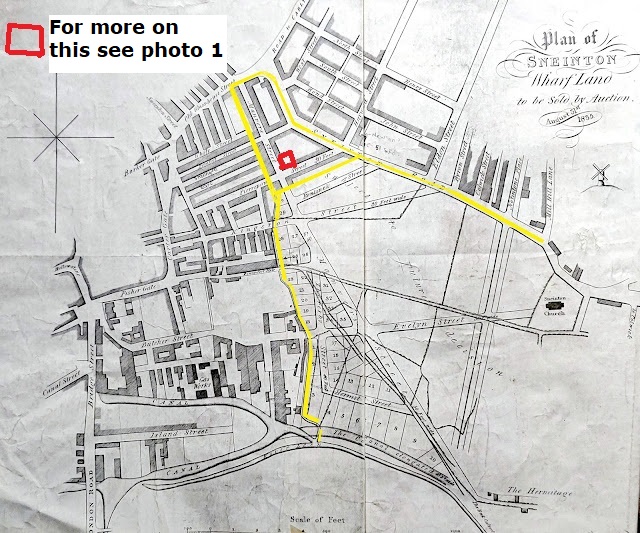

| Fig.1 |

According to Mellors, a few houses

were built at New Sneinton in 1804 (1); he elaborates no further

than this and acknowledges no source for his information. H Wild's map of 1820 shows a few buildings to the East of Carlton Road

and Sneinton Road, standing on John Musters' plot 13 (Fig.1). Also

shown is the road leading from Sneinton Road to Bond Street and West

Street.

|

| Fig.2 |

Unfortunately the map does not

extend to cover any more than this, and it is difficult to know how

far the building extended at this time. Some indication is given by H

M Wood's map of 1825. (Fig.2) This shows that the grid of streets comprising

North Street, South Street, West Street, Bond Street and Haywood

Street has been laid out but is largely free of buildings, beyond the

few shown on Wild 's map and a couple of blocks on Bond

Street and North Street.There are no buildings at all in the

area on the enclosure map of 1796, and so if Mellors' 1804

houses do exist it is reasonable to suppose that they are among those

shown on Musters' plot 13. The pre-1820 houses were at that time a

good distance from the town, and would have been situated amongst

gardens and orchards on elevated ground and at this time, therefore,

perhaps deserved the title, 'handsome village'. But building in

earnest began around 1825, when the building line crept eastwards

past Water Lane and Carter Gate, to the River Beck and the Sneinton

Boundary.

|

Fig. 3 H M Wood's Map 1825

Showing the 1820 building

line in red |

H M Wood's map of 1825 shows

the grid of streets on Musters' plot 13, mentioned above, and it also

shows that Lord Manvers' plot between the Beck and Sneinton Road had

been prepared for building. A couple of houses had been already

erected on plots at the corner of Manvers Street and Old Glasshouse

Street (now Southwell Road), and at the corner of Manvers Street as

far as the Beck. Pierrepont Street had been laid down to join Water

Lane and Sneinton Road, passing to the South of Earl Street. Manvers

Street had been laid between its junction with Glasshouse Street and

the intersection with Pierrepont Street. Pomfret Street had been

extended across the Beck and the Sneinton boundary as far as Manvers

Street, and Eyre Street continued its route to Sneinton Road.

In 1820 the block between Old

Glasshouse Lane and Pennyfoot Stile appears to to have had building

in progress upon it, and similarly the block between Gedling Street

and Old Glasshouse Lane. By 1825, in the former block, houses had

been erected along the full length of Pomfret Street, white Street,

Earl Street and Stanhope Street, and were crowding up against the

Sneinton boundary along the West side of the Beck. In the latter

block, Nelson Street, Pipe Street, Brougham Street, Sheridan Street

and Finch Street had been completed. Building had progressed as far

as it could to the Northeast in this block, for beyond the row of

back-to-backs on the North-eastern side of Finch Street lay the Clay

Field. To the Southeast of the block lay Earl Manvers' close.

Earl Manvers began to dispose of

this close of land in 1823 and early 1824. The Nottingham Journal

carries advertisements offering for sale building land in lots of 200

to 1000 yards.

'The whole will be laid out with spacious streets,

commanding an immediate communication from Fisher Gate, to the upper

part of New Sneinton, and affording most desirable sites for private

dwellings, factories or malting offices' (2)

The land was sold,

according to Mellors (who gives 'papers in the hands of Mr W F

Grundy' as his source) subject to conditions that the houses built in

Sneinton should be not less than three storeys high above the surface

of the ground and must have 'front bricks and sash windows'. (3)

The streets were set out as being 24, 27 or 30 feet wide (4). This

land was of rather poor quality, being low and difficult to drain. It

fetched 11s6d to 24s9d per square yard (5) – not as high as that

inside the town (36s at its highest rate) but considering distance

from the town and the poor quality of the land, not a bad price.

Mellors regrets that 'The care

exercised in [the conditions upon building] was not accompanied by

any forbidding cellar kitchens or back-to-back houses or narrow

entries or insanitary arrangements (6). And it is interesting to

compare the housing on Musters' plot 13 with that on Manvers' as it

stood in 1828-9. Chapman rightly observes that the proportion

of back-to-back houses in the area was lower than that in the town:

what back-to-back housing does exist, exists largely in Manvers'

plot. Byron Street and Camden Street show that Musters' land had no

covenant prohibiting back-to-backs (unlikely anyway at this time).

Musters' land is of a better quality than Manvers', being elevated,

surrounded by open country and isolated from the lower part of the

town. So it seems reasonable that a fair standard of building would

be erected in order to attract the higher rents paid by those who

could afford to be more selective in their choice of area.

Manvers' plot, on the other hand, is different from the lower part of

the town only insofar as it was under different ownership, and lay

across the trickle of water known as The Beck, and across the Sneinton

boundary. Thus the building between Sneinton Road and The Beck, and

in particular that between Manvers Street and The Beck, can be

regarded in everything but name as an extension of Nottingham's lower

congested area.

The first buildings to appear on

Manvers' close were at the junction of Manvers Street and Southwell

Road, to the West of of Manvers Street and between Manvers Street and

The Beck. These were built by Joseph Nall, a local builder, who

bought the land in 1824. They are shown on Wood's map of 1825 (Fig.3). The

plot measured 40ft in length and 20ft wide at its narrowest end. Nall

managed to cram four houses into this space (7, Fig.4). These were

'through' houses, surrounding a tiny courtyard whose Southwest facing

side was blocked off by the building across The Beck. (Which as yet

was not culverted.)

|

| Fig.4 |

Wood's

map of 1825 needs to be handled with care with regard to Sneinton. It

seems that the map must have been surveyed fairly early in the year

and, because of the building activity which took place in Sneinton

during that year, omits much that can claim to have been there in

1825. By the end of 1825, the whole of the land bounded by Southwell

Road, The Beck, Pomfret Street and Manvers

Street had been built upon (8, Fig. 4), although this is not shown to be

the case by the map. The block measured 216ft x 50ft x 220ft x 20ft, and contained thirty houses: eighteen of them paired into

back-to-backs, facing upon Manvers Street and Pomfret Street on the

outside and Beck Yard on the inside. These back-to-backs were a

continuation of those already built in White Street and Pomfret

Street. They were of the standard three-storey design, arranged in

terraces backing onto each other so that they had only one wall not

shared. This style, says Chapman, was widely adopted in Nottingham

between c1784 and 1830 (9).

|

| Fig.5 |

They were coming onto the market by

mid-1825:

'To be sold by auction … all those

17 freehold dwelling houses (newly erected and substantially built)

in Pomfret Street and White Street in the town of Nottingham …

[producing] an annual rent of £166 per annum: and also, all those 14

freehold dwelling houses adjoining to the last mentioned messuages

and situated in the parish of Sneinton … producing an annual clear

rental of £145 …' (10).

Press advertisements also show that

property was coming onto the market in the Pierrepont Street and

Kingston Street areas, which are not shown to be built up by Wood's

map of 1825:

'Six newly erected dwelling houses

situated in Kingston court, near Pennyfoot Stile, five storeys high,

all in the hands of good tenants; are very substantially built,

well-timbered, and have a pump of good water for the use of the

estate. Each house has a low kitchen, house place [living room?]

chamber [bedroom], workshop and attic.' (11).

This seems to be a good example of

estate agent double talk: no buildings in the area could have been

described as being five storeys high. Ground floor, bedroom, workshop

and attic or 'cockloft' was standard. The matter seems to be resolved

by the vendor's inclusion of the 'low kitchen' into the height above

ground of the dwelling. The low kitchen would have been a basement or

half-basement kitchen such as those which irritated Mellors. The

workshops were built 'for the accommodation of twist machines.'

As with Manvers' plot, Wood's map is

also misleading about Musters' land on the other side of the road.

Press advertising shows that at least one large block in the South Street

area of plot 13 was tenanted at the beginning of 1826. The

advertising bears out the suggestion made above that there was

a difference of standard between Manvers' plot adjacent to the

Nottingham boundary and Musters' plot, higher and having one side

looking over the Clay Field. In February 1826 a block fronting onto

South Street containing houses, a brewery and a malthouse was offered

for sale, ready tenanted (12). The houses were described as being '

… commodious … with gardens … bake-houses, front shops, factory

adjacent thereto, and outhouses'.

|

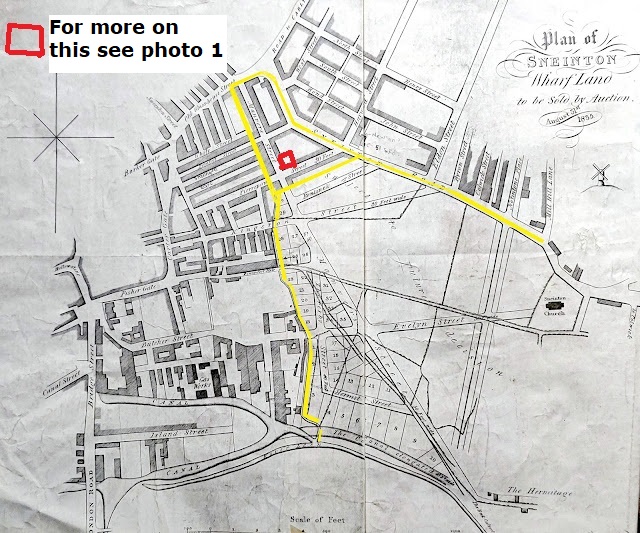

Fig.6 1881 OS 25 inch

___ Sneinton - Nottingham Boundary |

Examination

of the 1881 25 inch OS map of the area (Fig.6) and of Staveley and

Wood's, shows that the portion of the Water Lane – Pierrepont

Street – Sneinton Road – Glasshouse Street block which lies in

Nottingham and outside Manvers' plot is comprised totally of

back-to-backs very closely packed. That part of Manvers' plot lying

between Manvers Street and The Beck, and which has already been

discussed, is composed of two thirds back-to-backs, while the

'throughs' are very closely packed. The story is similar with that

part of Manvers' plot which lies between Manvers Street and Sneinton

Road. There are 'throughs' with adequate yard space at the junction

of Manvers Street and Southwell Road (then Old Glasshouse Street),

and also a row of 'throughs' with rather less yard space along

Sneinton Road. Behind these facades lie the tiny courts and

back-to-backs. Thus Manvers' plot seems to have been much the same as

the congested lower town, with the addition of a few more desirable

residences along the new, wide, roads. |

Fig.3 1881 OS 25 inch map

showing part of Musters' plot 13 |

Examination of the same maps shows

that Musters' plot contained only through houses at this time, all

with adequate yard space, and, if the advertisement is right, some

with gardens. These were bigger than the back-to-back type, and, with

windows running along the sides of their workshops, could accommodate

more lace machines. Nearly all of these survived until 1958, when

they were removed during slum clearance (See Photos 1 - 4).

The vendors' descriptions of property

on Musters' plot are generally more fulsome than their descriptions

of property on Manvers' – going into details of scenery and

elevation, employing adjectives such as 'commodious' and 'spacious',

and are 'suitable for retirement' (13). They are unlikely to be

subject to 'annoyance from other erections' (14). 'Substantial' and

'well built' is about as far as anyone goes in describing property on

Manvers' side.

How much was paid in rent by those

living in the area is difficult to discover, as is the case,

apparently, with Nottingham as a whole at the time. Chapman has

compiled a table, from what evidence exists, of rents paid for

working class housing in the city. (Table 1).

Table

1

|

Rents

charged for working class houses in Nottingham 1825-50

|

|

|

2

Storey

|

3

Storey

|

Houses

of a 'Better Sort'

|

|

1825

|

-

|

2s6d

|

-

|

|

1829

|

1s6d

|

-

|

-

|

|

1833

|

2s3d

|

-

|

3s6d

|

|

1845

|

1s6d

|

2s2d

|

3s0d

|

|

1850

|

1s9d

|

2s2d

|

-

|

|

Source:

Nottingham Review 30 September 1825, 17 April1829, 28

February1845, 25 January 1850; Nottingham Journal 8

November 1833

|

The only evidence of the rents paid

in Sneinton is that given by the advertisements for investment

property, and most of these are only useful with regard to property

on Manvers' plot. What evidence there is suggests that rents for

back-to-back houses were around the 4s0d mark – a very high sum

indeed, compared with Chapman's average. They all come in the three

storey category which Chapman prices at 2s6d. There may be some

explanation for this high figure (which is based on flimsy evidence

anyway) however. This was the time when the boom in house building

was at its height, and when the lace trade was most prosperous. All

the new property coming on the market was ready-tenanted, suggesting

no shortage of demand. The district was most definitely predominantly

occupied by lace makers (see below table 2), who at this time could afford high

rents and were a causal factor in the housing boom. Further,

Chapman's figure is an average, and it could be a misleading average,

for it may consist of two widely different basic elements. As he

himself says, the highly prosperous lace-makers of the 'twenties

occupied different properties to the depressed frame-knitters:

'Inevitably this divergence of

fortune was reflected in housing conditions. … By the early 1830s

the two social groups lived in houses of different sizes and

qualities, but also in different parts of the town … the lace hands

lived and worked in the upper storeys of substantial houses … in

the approaches and the back streets … and the better houses of the

lower town … numbers of them moved out into the new industrial

villages. The framework knitters lived in the more obscure courts and

alleys. Descriptions obviously refer to … back-to-backs built in the first stages of industrialisation'. (15)

The difference in rent paid by these

depressed knitters and the rents paid by lace hands for newer,

better, property could account for an average which approaches neither.

As to the basic stimulus for the

growth of New Sneinton in the 1820s it can be safely said that it was

the boom in the lace trade. On the sheets of signatures to the

agreement to limitation of hours organised by Felkin in 1829, there

are signatures belonging to 87 owners who give their address as

Sneinton.

According to White's Directory of

1832, the number of new houses built during the decade was 'upward of

a hundred' (16). The appearance of 87 machine owners and of 100

houses simultaneously can only mean that they were occupying the new

houses – all of which (except for the small number of larger middle

class houses) had second floor workshops.

The signatures are of no help in

placing the owners: addresses are merely given as 'Sneinton', 'New

Sneinton', or 'Old Sneinton'. White's Directory is of some little

help however, giving addresses (in 1832) of 56 bobbin net makers

(17). The majority - 37 - of these have their addresses on Musters'

plot 13 (Table 2). Only 5 are definitely on Manvers' land.

Table 2

|

Distribution

of Bobbin-net makers at New Sneinton as listed in White's

Directory 1832

|

|

Windmill

Hill

|

11

|

These

are on Musters' Plot 13.

|

|

North

Street

|

7

|

|

Bond

Street

|

6

|

|

South

Street

|

9

|

|

West

Street

|

2

|

|

Haywood

Street

|

2

|

|

Pierrepont

St

|

4

|

These

are on Manvers' land.

|

|

Manvers

Street

|

1

|

|

Sneinton

Road

|

8

|

These

could be on either Musters' or Manvers' land depending on which

side of the road they are.

|

|

Carlton

Road

|

6

|

Even considering White's Directory

and the hours agreement together, however, there is little in the way

of hard conclusions to be had. Lace machine owners are not

necessarily bobbin net makers, and frequently bobbin net machine

operators rented their machines or operated them for a middleman.

What information can be had?

Felkin's list (18) tells us that the 87 owners had between them 152

machines. One owner had eight, one six and a number, four. 45 had

one, and there was a fair proportion of owners of two or three. There

was no sharing of machines.

It is reasonable to suppose that

those owning one or two machines operated them themselves, possibly

with the help of employed hands, in their own homes. This may well be

the case with owners of three machines (19). The owners of four or

more machines would certainly have had machines and work farmed out

to other operators in other houses, and there is nothing to rule out

the possibility that they did not operate them at all themselves –

perhaps even living in the larger middle class houses near the old

village.

If the criterion of ownership of two

machines or fewer is applied in classifying owners who operated their

own machines in their own homes, this makes, according to Felkin's

list, 73 owner-operators. White's list is obviously incomplete, which

is to be expected of a county directory anyway, and which fact is

shown up by comparison of the population figures and the number

included in the occupations guide. Some sort of selectivity must have

taken place. Bearing in mind that the practice of farming out

machines and work was common enough, and also bearing in mind that

the owner-operator would be a person of greater substance than an

employed operator, perhaps it can be said that this selectivity

operated in favour of those operators who owned their own machines.

These would be the sort of people solicited for inclusion – or who

would apply for inclusion. From this and from the fact that the

greatest number of bobbin net makers in White's Directory occupy

houses on Musters' plot 13, a tentative conclusion may perhaps be

drawn. Assuming White's Directory to be selective in favour of the

more prosperous lace-machine operators, there are additional grounds

for believing that the area which grew up on Musters' plot was

'better' than than that which grew up across the road on Manvers'

plot. The suggestions are that there were larger, more spacious

houses, fewer back-to-backs and, if the reasoning and evidence in the

previous paragraph are sound, a higher number of people with capital

of their own, i.e. bobbin-net machines, on Plot 13 than on Manvers'

plot.

***

Sneinton, a small village a mile or

so to the East of Nottingham, took its first major step on the road

to becoming an urban quarter in the 1820s. In the Nottingham area was

concentrated an industry organised as a domestic outwork system. The

industrial revolution gave a tremendous boost to this industry which,

as a making-up industry, was able to profit from the abundance of

cheap factory-produced yarn. A degree of prosperity in a domestic

industry gave rise to a building boom of considerable proportions in

the middle of the decade. A building boom in a city which could not

expand outwards on most of its perimeter caused a high degree of

congestion within the city. As pressure built up within the

Nottingham boundary, the building line burst through into Sneinton,

adjacent to Nottingham, and unencumbered by old open field

restrictions.

Basically then, the first phase of

Sneinton's growth differed from the first phases, occurring at the

same time, in the growth of other areas which now form quarters of

Nottingham, such as Hyson Green, Radford and Carrington. Whereas in

these areas growth was brought about by migrants from Nottingham,

driven out by conditions and prices in the town, the growth of New

Sneinton at this time was was one and the same with the growth of the

town. In quite a literal sense, Nottingham spread into Sneinton.

Having said this, there are some

small grounds for considering the possibility that Sneinton Road

formed a sort of demarcation line with an area more akin to the

'handsome villages' on the eastern side, built on Musters' plot, and

a continuation of Nottingham's congested lower area on its western

side, on Manvers' land.

This study is by no means an

exhaustive study of Sneinton's first growth phase. A long and

detailed study of all the deeds to the area, which are becoming

available as demolition progresses, is a priority. Perhaps when this

is done, the next phase in the history of Sneinton, with the hard times in the lace industry of the late 'thirties and the 'forties,

and with the degeneration of the area into a slum, can be considered.

***

Map Accompanying the Sneinton Enclosure Act 1792

(Note: Lord Newark became Earl Manvers in 1806)

Development within Enclosure plots by 1829:

12, 13, 14 - John Musters,

15, N - Lord Newark (i.e. Earl Manvers)

%20-%20Boundary%20-%20Plots%2012%2013%2013%2014%2015%20N.jpg) |

| Staveley and Wood's Map, surveyed 1829, published 1831 |

Map accompanying a flyer for a land auction, August 1835

This plan shows Nottingham's buildings crowding up against Sneinton's boundary at the River Beck; across on the other side, Lord Newark is selling his next trenche of building land. It is a fascinating glimpse into events as they happen - lanes, footways and hedges are still there, streets are conjectural and the east side of Manvers Street is 'Subject to future decision'. Surveyors have been out measuring and draughtsmen have divided up the fields into numbered plots ready for the builders to come and bid for them. See photo 1 for an example of what was built on it.

(Note: this map did not appear in the original dissertation as it was discovered some years after it was submitted.)

|

| Photo 1: Manvers Square, pictured in 1931, a typical enclosed court with tunnel entrance, on Manvers' land, shown as already built in the flyer of 1835 (above) |

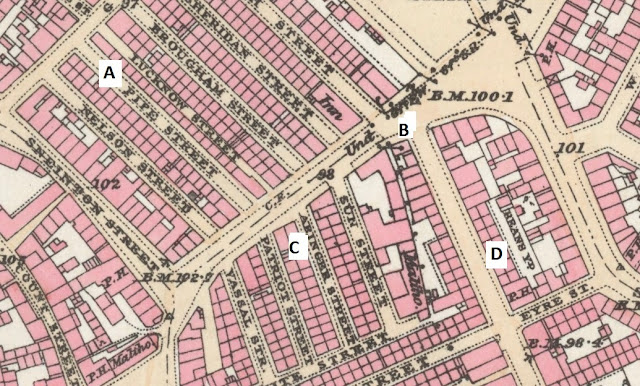

The map below shows Manvers Square in its location at the corner of Pierrepont Street and Manvers Street.

|

Photo 2: Manvers Square as shown on the OS large scale town plan of 1882.

|

|

Photo 3: Houses on Bond Street, Musters' plot 13, prior to demolition 1950s

|

|

Photo 4: Houses on Musters' land at the junction of North St and Carlton Rd in the 1950s showing large upper storey workshop windows

|

|

| Photo 5 |

Photo 5 shows the corner of Manvers Street and Southwell Road - the site of Joseph Nall's houses.

.

Wood's 'Gas Bill' map of 1841, accompanying an act of parliament for supplying gas to the areas beyond the town, shows development progressing on Manvers' land. Also, there are houses at Sneinton Elements at the end of Windmill Lane, and at the junction of Carlton Road and Alfred Street - the Clarence Street area. The map also demonstrates the restricting effect of the unenclosed commons - soon to be addressed by an enclosure act in 1845.

|

| H M Wood's 'Gas Bill' Map 1841 |

End of the Dissertation

But for more of Sneinton and me scroll down and select 'Newer post' or the Left arrow.

Notes

1/ op.cit p.10

2/ Nottingham Journal 27th December 1823 and subsequent issues to 31st January 1824, also 5th June 1824

3/ibid, and deeds to property at At Manvers St. Central Library Archives

4/ Ibid5/ Ibid

6/ Ibid/

7/ Deeds to the property at City Library Archives M21,385 to M21,4145;

8/ The above deeds and also deeds to 6-26 Manvers St, and Beck Yard 1-5 inc.; Manvers St 28-34 (even); M21,436-21,503; M21,467-M21,485

9/ op.cit p.140 (Revision)

10/ Nottingham Journal 28th May 1825

11/ op.cit 8th October 1825

12/ Nottingham Journal February 2 1826

13/ Nottingham Journal 20th November 1824

14/ op.cit 22 April 1826

15/ op.cit p.151 (revision)

16/ p687

17/ p689

18/ Which, in view of the fact that it so narrowly missed the 7/8 majority can be regarded as being almost a complete list. The better houses were sometimes advertised as having room for 3 machines, e.g. Nottingham Journal 8th October 1825

19/ The better houses were sometimes advertised as having room for 3 machines, e.g. Nottingham Journal 8th October 1825

Maps:

H Wild, 1820

H M Wood, 1825

Wood's Gas Bill Map

Staveley and Wood, surveyed 1829, published 1831 Staveley and Wood's Map of Nottingham, surveyed 1828-9, published 1831: a high resolution download is available at

OS 25 inches to 1 mile, OS Large Scale Town Plans and many others can be seen at the National Library of Scotland's brilliant interactive collection of historic maps at: https://maps.nls.uk/

Photos:

%20-%20Boundary%20-%20Plots%2012%2013%2013%2014%2015%20N.jpg)