I wrote the dissertation just over 50 years ago in 1973, as part of my B/ed with History degree at Trent Polytechnic, which was at that time in York House, Mansfield Road. Next door, Victoria Station was being shovelled out of the way to make room for the Victoria Centre.

There was a vast amount of that sort of thing going on then. This screenshot from the title sequence of the 1973 BBC sitcom, Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads? shows a scene we all knew well. Children play in a remnant of the old and familiar; beyond the empty windows the future rears up. Whole areas of the city were being remade. The walk into town from my parents' house took me through a rubble strewn wasteland. Crowded areas of houses shops and pubs were gone. Their streets lingered a while, defining plots which looked far too small to have ever accommodated them.

This, of course, wasn't the first slum clearance programme, but it was by far the biggest and most comprehensive. During the late nineteenth century there had been attempts to relieve the instant squalor created by cramming shoddy housing into restricted space to accommodate a rocketing population.

Though sometimes locally successful, these projects came nowhere near the scale needed to make any impression on the problem - and unaffordable rents caused by the requirement to turn a profit excluded many people who might have benefitted from them.

By the twentieth century, governments had accepted that they had a responsibility in the matter and funds and legislation began to be provided for slum clearance and council housing. (1)

|

| Fig.1 |

Beginning in 1919 on Stockhill Lane, quality council housing started to appear. The council bought land at Aspley Hall and work began on the Aspley estate, where, later in the century, I was to work for many years. The era of council estate building was soon well under way – with time out for another world war.

In the 1950s things got going again, and I was now around to take notice. I lived the first 11 years of my life in that later Victorian phase of development, Sneinton Dale. I remember walking down the old Sneinton Road to the Albion Chapel Sunday School, Victoria Baths and Sneinton Market, where my Uncle George had a stall. In time, the process that had begun on the other side of Manvers Street thirty odd years before resumed on this side. Houses and shops emptied out and the demolishers moved in.

After Sneinton my family moved to Thorneywood - Gordon Road, Bluebell Hill and St Ann's Well Road became the background to my life for the next fourteen years. Then it was their turn for demolition. And during my time at uni - when I was writing the dissertation - new housing was being built there. Soon, I was to spend five years teaching at schools in the newly built (and newly named) St Ann's.

Below

In this 1931 photo the newly erected City Transport development is viewed from across the road in Pipe Street which, too, was soon to be redeveloped.

The view from the same place in 2025: The Sneinton Market Avenues, created in the 'thirties as a wholesale fruit and vegetable market, are now 'Nottingham's Home for Creative and Independent Businesses' (3)

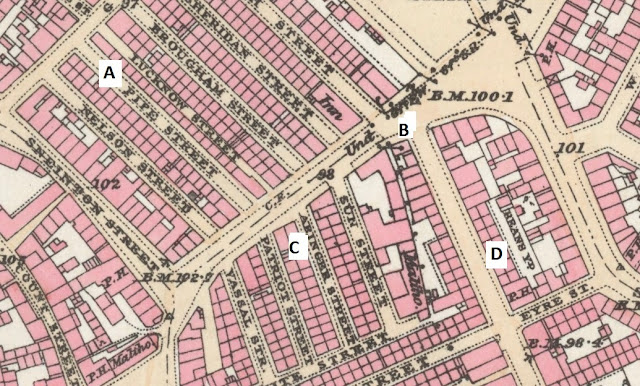

Below: OS map 25 inches to 1 mile 1881

A/ Pipe Street, demolished in the thirties, showing the approximate point from where the picture was taken. The street next to it, Nelson Street, still exists.

B/ Nall's plot, between Manvers Street and the Beck. This was obliterated by the 1920s City Transport development.

C/ Area redeveloped in the 1920s.

D/ Much of this block, between Manvers Street, Southwell Road, Sneinton Road and Eyre Street remains, including the William IV pub on the corner of Eyre Street, now known as the King Billy.

Below: Detail from a flyer offering property for sale between Abinger Street and Patriot Street ('C' in map above) on 29th September 1897 'to wind up a trust'. (4) Had a photograph been taken from the same spot a few years before that 1931 picture was taken, these properties would have been seen at the end instead of the transport building. Dwelling houses were sharing this tiny space with a slaughterhouse, a dyehouse and a butcher's shop. The shop and dyehouse were making £23.8s.0d (£23.40p) p.a. rent and the houses were making £53.6s.0d (£53.30).

Sneinton Road as it was in 1908 and still was when I was a child. (5)

Sneinton Road as it was when I wrote the dissertation. The remaining block from the1820s development (marked D on the 1881 map) can be seen at the bottom. The Albion Chapel remains, on the left.

Sneinton road in 2025 - the 1820s buildings, tidied up, can be seen down at the end.

II

It wasn't all about slum clearance though.

The number of people being displaced by demolition was only one of the drivers of demand for new houses at that time. After legislation was passed in the 1870s allowing councils to set building standards, and after the city boundary was extended in 1877 to take in some adjacent areas including Sneinton, better quality terrace housing went up all around the city including, of course, Sneinton Dale. This was intended as rental property, mostly for working class people, much of it built by small scale operators as an investment. (6) My maternal grandparents never owned a house but always lived in decent rented houses in Sneinton - as did my family until I was eleven. All my schoolmates at that age were living in rented accommodation, some in the decayed properties of the first phase of building; some in the better ones in the Dale. Very many of these people would soon be going out into the world and would be aspiring to move up to the next level - home ownership.

The 1973 BBC sitcom, Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads?, written by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais and starring James Bolam and Rodney Bewes, isn't only very funny – it's documentary. The series deals with two young working class men emerging from their carefree life as 60s teenagers to face adulthood and responsibility in that shifting world. Terry, home from overseas army service, is shocked and bewildered by the wreckage of the world he left behind two years before. His mate from schooldays, Bob, has stayed home and is thriving, with a desk job in the booming construction industry. He is engaged to be married and soon to move into a new-build bungalow. Taking Terry in hand, Bob tries to get him to embrace the new. Terry, appalled at what he sees as selling out, struggles to reconnect Bob with his youthful ideals, unconsciously subverting his new lifestyle.

That new lifestyle is poignantly evoked in Ray Davies' 1969 song, Shangri-La, by the Kinks:

'Now that you've found your paradise

This is your kingdom to command

You can go outside and polish your car

Or sit by the fire in your Shangri-La.

Here's your reward for working so hard

gone are the lavatories in the back yard...'

Bob wants more than a continuation of back street terrace life, outside toilets and a single cold tap in the kitchen. He sees that by working hard he can become a member of the home owning class. That would describe just about everyone I knew then.

The 'Shangri-las', of course, weren't built on those demolition sites. They were usually built on greenfield sites around the edge of the city. The mix of people occupying them was varied – skilled tradesmen, higher earning factory workers, white collar workers, couples getting away from living with parents and so on. What they had in common was a decent wage and a degree of job security, enough to qualify for a mortgage.

Mortgage lenders were sniffy about my job though – shop assistant – so in the late sixties when my fiancé and I wanted to marry and move into our own Shangri-La we had to embark on some ferocious saving. If we built up a really juicy deposit in a building society account they just might consider us. But we entered our names on the waiting list for a council house just in case.

Despite having failed it at O Level, I had always been interested in history. I read a lot about it and had been intrigued by childhood brushes with historic places. (See my Like Enid Blyton posts) I lived among streets and pubs carrying the names of Georgian and Victorian military and naval heroes. I must also give some credit to one of the shop managers I worked for. He ran a tight shop and worked us hard. But when trade was slack he would ease up and give us down time. At those times he would send one of us to the library for a pile of books, and he liked history. Inevitably we would end up discussing and arguing about what we were reading.

So of course, at uni, I opted for History as my main subject. Then, early on in the course, I encountered one of those life changing books. It was Victorian Suburb: A Study of the Growth of Camberwell, by H.J.Dyos, published in 1966. I was gobsmacked. It was history like I'd never seen before. It could have been the story of my world – the people who made Victorian suburbs like mine had discoverable names and lives. More – they were like people I knew (7) Inevitably, I chose the history of working class housing for my in-depth study, focussing on Sneinton.

And, totally by chance, I moved back to Sneinton – a bedsitter in a characterful old house on that street of characterful old houses, Castle Street. Home for the next seven years.

I was back to walking down Sneinton Road, this time to York House. Now, though, the Sneinton Road I knew as a kid was gone.

And I began to find out how it got there in the first place.

***

For more of Sneinton and Me scroll down to the end and select 'Newer post' or the left arrow

(1) Housing, Town Planning &c Acts, 1909 and 1919 for example. And Homes and Places by Chris Matthews is essential reading - a thorough yet highly readable history of Nottingham's council houses.

(2) See Sneinton and Me 5

(3) www.sneintonmarketavenues.com

(4) Stephen Best, Nottinghamshire History website

(5) Nottingham City Archives.

(6) See Sneinton and Me 7 - Peter Elliot Bates

(7) See also whysHistory, The Past is Right Behind Us

Photos

Pipe Street 1931- https://picturenottingham.co.uk/

Sneinton Road - Stephen Best, Nottinghamshire History

The rest - WhysWhys

Maps - National Library of Scotland, https://maps.nls.uk/